Sinéad Burke On The Power And Influence Of Disability Representation

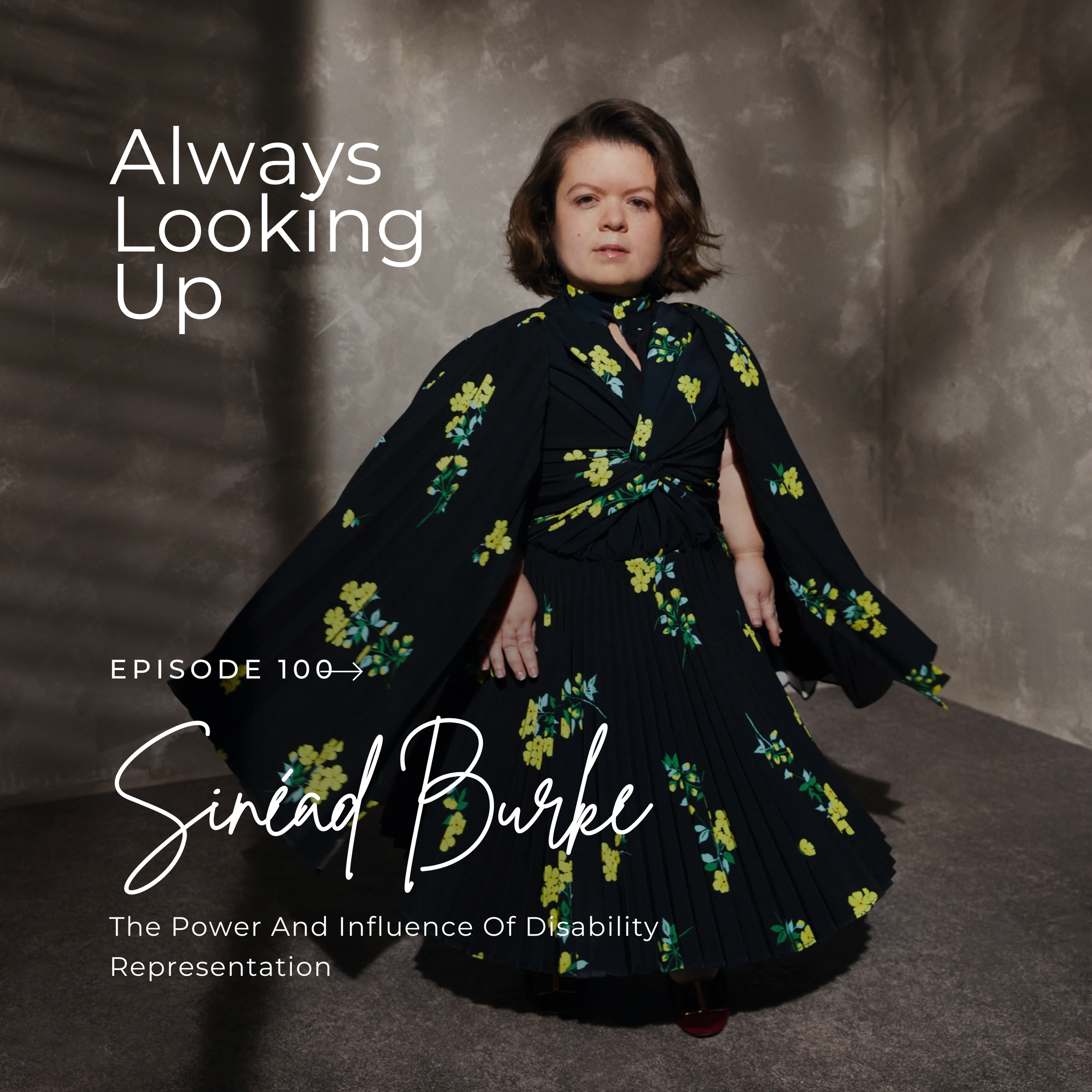

Image Description:

Sinéad Burke, a white, queer, little person, standing in a room in front of a grey, textured wall. With her brown bob curled into soft waves, she is twirling in a black, full length Richard Quinn dress with a pleated skirt and a yellow and green floral print. The dress has a matching cape that is floating out around Sinéad’s shoulders as she moves. She is wearing her own oxblood shoes by Ferragamo. Overlaid is the text “Always Looking Up. Episode 100 -> Sinéad Burke, The Power And Influence Of Disability Representation

Jillian Curwin: Hi everyone. Welcome to Always Looking Up, the podcast where no one is overlooked and height is only a number, never a limit, hosted by me, Jillian Curwin. Each week I will be having a conversation about what it is like to live in a world that is not necessarily designed for you.

In this week's episode, the 100th episode, I sat down with Sinéad Burke. Sinéad is an Irish author, academic and disability activist. She's the founder of Tilting the Lens, a disability led consultancy that advises major global brands, guiding them in their move from awareness to action by creating more acceptable practices, policies, products and services, places and promotions. We discuss her career path from fashion blogger to CEO, the shift in asking the fashion industry to design for us, the disabled community, to design with us, the power and influence of disability representation, not just in fashion, and much, much more. Let's get into it.

Hi Sinéad.

Sinéad Burke: Hi, Jillian. How are you?

Jillian Curwin: I'm doing well. How are you?

Sinéad Burke: I mean, I feel like, in this moment, I should probably perform a sense of “I'm great,” which I am, in some extent. But to be very honest and transparent in the theme of your podcast, I'm actually pretty tired at the moment. I am hoping to get some rest this weekend, but I am genuinely thrilled to be in conversation with you. So, as regards to that, I'm doing really well.

Jillian Curwin: I'm very excited to be talking with you as well. I imagine we have a lot to be talking about, and probably some of the reason as to why you are tired and in need of rest.

This is a very special episode, not just because I am talking to you, but because this is the 100th episode of Always Looking Up so I am incredibly honored that you are my guest today. And to start, why don't you tell my listeners a little bit about yourself?

Sinéad Burke: My name is Sinéad Burke. I am the CEO of Tilting the Lens, which is an accessibility consultancy. I am based just outside of Dublin in Ireland, but currently I am in London in a hotel room.

But speaking of accessibility, I should start by giving a visual description of myself. I am a white, cis-gendered woman who uses the pronouns she and her. I am visibly and physically disabled, I am a little person, and I identify as queer and disabled. I have brown, shoulder length hair, which today has not been blow dried. So it is kind of chaotic in its formation. I am wearing a fluorescent yellow sweatshirt which has a round neck and on the left hand side there is a Tilting the Lens logo. I am wearing black pants because I have been in my consulting role all day, so slightly formal, and a pair of Birkenstocks because my feet hurt from wearing high heels. And I am sat in kind of a cream room where there is wood paneling to my right and a bed behind me with a painting that I cannot decipher from this angle. But that's me.

Jillian Curwin: I love that. And I will give a description of myself. So I am Jillian. I am a white, cisgender person. I am a little person or person with dwarfism. I have brown hair that is behaving today, it normally does not behave. And I'm wearing a pink lip stain. I'm wearing a black tee shirt that says AUF AUGENHOEHE in white lettering, which is a brand we love, they’re brilliant. Behind me is a black couch with black and white pillows and a navy blanket. And over my other shoulder are windows with, that are very filled with sunlight right now. And hopefully we will not hear sirens through them. Fingers crossed.

Sinéad Burke: It's gorgeous. There is so much light in your apartment.

Jillian Curwin: Thank you. It's, it's beautiful out today in New York City. And we've been kind of like, waiting for this. It's definitely been like, cloudy and gross these past couple of weeks. So now the sun has really made its presence known here and we're very happy about it.

Sinéad Burke: It's gray in London and has been miserable all day, but I'm hoping the sun comes very soon.

Jillian Curwin: I'm going to send some to you.

Sinéad Burke: Please. Thank you.

Jillian Curwin: You got it.

So I have two initial questions for you. The first is, how do you define being a little person?

Sinéad Burke: Gosh. I define being a little person as fundamental to who I am. I am a person who has grown and evolved with my use of language, and how I describe myself, and how I identify. And I think if you had asked me maybe 15 years ago how I describe myself, I would have just said that I am Sinéad, never really using language of disability, not because it was something that I felt a sense of shame over. But I was never, I think I was just so wanting to be myself that that distance was not conscious but, or deliberate, but existed. I think I have moved to describing myself as a person with a disability. I now describe myself probably as a disabled person. I think so much of my personality and skills have shaped, have been shaped because I'm a little person and have dwarfism. I think I would be a very different person today with different ambitions and a different career if I wasn't a little person and see it as a real strength. Though of course there are challenging moments and periods, but I am very proud to be a little person and would not like to be anyone or anything else.

Jillian Curwin: There's so much you said in that that I want to talk about and you kind of bridged into the next question, which is then how do you define being a disabled person or person with disability?

Sinéad Burke: It's interesting. As somebody who has a visible and physical disability, much like you, I'm so rarely aware or conscious that I am disabled unless there is a moment of friction, whether it's in the built environment or with people, wherein…it is incredibly obvious to me and everybody else that I have a physical disability. So for example, I'm in a hotel room, and this is an accessible room, it is actually a very beautiful, accessible room. But despite that, there are still challenges to the accessibility. Because again, how we define accessibility is often based on code, or compliance, or starts with the assumption that the user is somebody who is a wheelchair user. And in this room I cannot see in the mirrors, in the bathroom particularly, and I am reminded when I come into this space that not only am I disabled, but I'm a little woman because of the ways in which the legislation, the designers, etc., are designing for a certain type of disabled person rather than with a collective of individuals. And I think that is an example of which is part of my quotidian experience as a disabled person that based on how I exist in my own body. I am often unaware of the fact that I am disabled until I am made viscerally aware of the fact that I'm disabled.

Jillian Curwin: You touched, you know, when you bring that up like, I think that is so true, particularly for us with our type of disability. And it's interesting because we don't know anything else. We don't know anything different. We've never lived in non-disabled bodies. And yet so often, you know, speaking for myself as well, I find myself in situations where I don't necessarily recognize that I'm disabled until society or until the environment that I'm in has to remind me. And I think that's part and parcel of why it took me so long to truly identify as disabled, because it was always, “Oh, you're just short, you're just different.” And, taking on disability as an identity, it was one, freeing in a way to be like, no, actually I need to be included in these conversations about accessibility, about inclusion. And you know, it's definitely kind of allowed me to say like, no, like this, it's like, it's also, it's okay. I feel like there is still such a stigma, and for some reason as little people, and maybe you could shed some light into this, like there is a stigma as to why perhaps we don't want to say that we are disabled even though the laws, while the guidelines for accessibility don't necessarily include us, the laws do say we are disabled as people with dwarfism.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah, I think you bring up such a good point that often we create this hierarchy of disability, or hierarchy of ability, and really value and prioritize, or seem to be more impressed by those who skew closer to the definition of non-disabled. And I think this is also true within the disabled community. I think within, and specifically within the dwarfism community or the community of little people, even within that, we often have a hierarchy of disability or identity.

Jillian Curwin: Mmmhmm.

Sinéad Burke: Whether that is little people who also have learning disabilities, little people who have different intersections of identity in terms of how they overlap. I think it's really important that we are explicitly conscious of the ways in which we don't further marginalize people who are already, who are already part of a marginalized community, and ensuring that we see ourselves as part of a collective. While yes, having a very clear sense of who we are as little people, but ensuring that we see the need for collaboration, for collective advocacy. And I think continuously reiterating the fact that disability is a neutral term, it is neither negative nor is it often positive in terms of how you frame it. And actually it is not, and does not make someone who identifies as disabled less because they are so. And I think this begins to challenge and unpick all of our assumptions around disability, particularly from childhood. I think when we acknowledge that, for example, 80% of little people are born to two non-disabled parents, how does that as a collective, inform our assumptions around disability? How do we even, you know, going back to the earliest conversations when parents or individuals are told that their fetus, their baby, their child is going to have dwarfism? Often those conversations are either framed by pity or “Don't worry, they're not really disabled in a way”, as if to make people more comfortable. And I think that further enshrines the ableism that often exists even within our own community. And the importance of us being a collective and being in community with other disabled people is incredibly important when we look to systemic change.

Jillian Curwin: Absolutely. And you brought up, you know, and we've talked about this before on the podcast the fact that there are 80% of us are born to average height parents. I am part of that 80%. And, you know, going back to what I said before with like, identifying as disabled, as far like, to my best recollection and I had…had and have wonderful parents. My father is no longer with us, my mom is here. She's wonderful. But like, growing up like, it wasn't necessarily disabled. I needed these accommodations, but it was always framed as I need these accommodations met because I'm a little person, because I'm a person with dwarfism. It wasn't necessarily framed as because I'm disabled. And, you know, that's, that’s, it would be interesting, and I'm sure that happens with a lot of us because, like you said, parents don't necessarily because again, there is a stigma, don't want to necessarily say that their child is disabled. That disability does, even though it is neutral, a lot of times non-disabled people see it as negative and, you know, just like when I like growing up, how our mindset and how this hierarchy, which, you know…I'm wondering, is this something that kind of we created as a community or is it something that because of how society, non-disabled people, see disability, that they kind of impose this hierarchy upon us?

Sinéad Burke: My gut sense is it's both neither and both at the same time in the sense that probably the little people community is a microcosm of wider society in the wider world. Yes, there are individual behaviors or traits that, that take shape there. And, you know, I'm conscious that you and I are here navel gazing at a whole community. And undoubtedly the little people community and non-disabled parents will disagree with us vehemently…

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: As is their right and as is their choice. But I think it is a microcosm of wider society. And I think if we look at how ableism presents itself in wider society, even if we look to a project that my team and I recently did with British Vogue, it was really important to us that we demonstrated as much as possible the breadth of disability. So, so often when we have representations of disabled people, it's often wheelchair users, people with prosthetic limbs, even little people. Rarely is it a Black person with a learning disability from an area of socioeconomic disadvantage, because that is often seen as their access needs are too complex, it is too disabling to include them within a project, or too challenging to have that representation be set up for success. And I think so often we again have to look to those who exist on the periphery, even within marginalized communities, and ensure that their lived experiences are centered. But I also think it's, it's part of the wider world. Right? We have even had challenges around the language that we use around disability. We have for too long and continue to use euphemisms. We talk about special education. We still talk about special education within our education sector.

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: And we talk about special needs, and we talk about differently-abled, and we talk about people's abilities rather than their disabilities. And we do that particularly in moments where, you know, we have the Paralympics coming up soon. Language from a global context will again differ.

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: And it's very challenging. And I think the one thing that we are always conscious of within our work is, particularly from a global context, is making sure that you're also not coming to this from a Western perspective and adjudicating to people what is right or what is wrong. But what we really need is a understanding of a community first approach to even something like language.

Jillian Curwin: I'm, I’m like needing a second to process that. We're going to touch on your work with Tilting the Lens, with British Vogue. We're going to touch on that. We're going to go a little backwards first before we do that.

Sinéad Burke: Sure.

Jillian Curwin: But it's so interesting how you talk about the Western approach to disability. because again, I think that is just predominantly what, how we frame and contextualize disability and you know, like the representation. It's interesting how you talk about, and I agree, that often when we see disability representation, it's the wheelchair, it's a person with a limb difference, it's an amputee and it is little people. But the little people representation is often quite different in the sense that it's not always with…there are exceptions, but there are definitely instances of little people representation and, that are not so positive and we don't necessarily see that with other disability. And, I mean that's rooted, we could go all the way back to like, the court dwarves and things like that, but it's just, it's so interesting and I think it kind of, it plays into like with, you know, just where do we see ourselves as little people where, you know, where the common type, which is achondroplasia which is the type I have and I believe it’s the type you have as well. We are non-disabled in the sense that we have four limbs and are ambulatory and, but that's our…what makes us disabled is not just our short stature, but that's the only thing that people see. And to a lot of people that's funny and it's, it's, I mean, there's, I mean, there's a lot that we could go off of there. And you also said before that people were probably going to disagree. And if you do disagree, I welcome to have that conversation. So please come on, let's talk about it. I love different, having differing opinions on the show.

But now let's rewind. Before Tilting the Lens where did you get your start? What was the spark that lit the match, that lit the flame for you and your work?

Sinéad Burke: Before we do that, do you mind if we jump back into the conversation that you were talking there about [unintelligible]?

Jillian Curwin: No, let's do it.

Sinéad Burke: I think that's really important. For me and, you know, I am continuously learning and in many ways continuously changing my opinion, probably because I'm in therapy, but also because I think that's the joy of getting older. I think one of the things that we as a community need to wrestle with, or have discussions about, is that our end goal and objective should be, I believe, greater and multiple formats of representation of people with dwarfism.

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: I think we also need to have conversations around agency and choice. I think when people choose careers, opportunities that are not to another's satisfaction, I don't think that we need to police or adjudicate what we believe to be right around based on our individual opinion. I think the challenge exists when there is only one type of representation of little people.

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: And I think what we need is multiple avenues wherein more and more representation of people with dwarfism exist so that there isn't merely one anecdote, one type of comedy, one type of understanding of what it's like to live with dwarfism. Because even as two white cisgendered women with achondroplasia, Jillian, I don't doubt that we have different beliefs, opinions, hobbies, pastimes. Right?

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: And we need to provide a multiplicity of representation and understanding. But I think the way in which we get there, which we often need to advocate for, which I think, just as a world, we don’t often don't have these conversations, is that this changes when there is representation of people with dwarfism, people with disabilities in rooms where decisions are made. So I think, yes, we need multiple format representation of people with dwarfism, but we also need that as CEOs. We need that as people who are chief financial officers. We need this as people who are content commissioners. And I think it's less about, for me at least, and again, I completely hold space in this conversation and with others in my DMs around the need for this to be just broader. And I think…

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: There isn't necessarily a right and wrong always, though some people may agree that there is sometimes. But I think if people are choosing and are consenting to projects and opportunities because they are interested, because they like them, because they provide revenue, I think we have to be graceful with ourselves.

Jillian Curwin: I agree, and I know what kind of things you're talking about and I agree. And I think we can't police them. I think that broader conversation about that though, is what conditions as society and the environment that we have created, that the predominantly non-disabled society have created…

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: That for some people this is their way to make money, it is their way to make an income. And I think that's where the broader question, that's where we can question and challenge, but not necessarily for the people who decide who that's what they want to do and what they want to pursue. That is their choice. And I wholeheartedly agree with that.

Sinéad Burke: Yes. So I think…exactly to your point, Jillian. I think it is about analyzing the ways in which there are so many systemic barriers for people to have as much choice as possible and for that agency to be central to every aspect of our lives, whether that is employment, health care, travel, joy and friendships, entertainment. And I think that's what we're all working to, that we can hopefully have just more and more choice.

Jillian Curwin: Absolutely.

And I want to pivot now into the work that you're doing, to kind of go back to one of the questions that I asked you. So we’re going to get to Tilting the Lens. I want to go back a little bit before to like, where did you get your start? What empowered you to start the work that you're doing?

Sinéad Burke: You know, it's funny. If I look back, I'm 32 now, I'm coming up 33 at the end of this year. If I look back at what I wanted to do when I was four or five years old, I don't think I would have imagined the career that I have been able to have thus far and hope to have in the future. But I do think in many ways there was key tenets that were part of my belief system as a person even then that are still true today. So I still believe in the power of education and training as a teacher and an elementary school teacher was incredibly fundamental to who I have become as a person, but also the understanding that when we think about theories of change, or if we think about ways of working that actually education is a way in which we move people from kind of awareness to action. Of course, I had none of that language when I was four or five and just loved that the classroom was a safe space for people to learn, to ask questions, to play, to explore. For me, I think having representation at home was incredibly important.

So, my father’s a little person. My mother’s non-disabled. Growing up in a home wherein my dad looked like me, was transformative in a way in which I probably can't even articulate, and even more so because I didn't realize how unusual that experience was based on the demographics of our community. And my father was born to two non-disabled parents, so he had a different lived experience to me. And it was both how he reared me, but also just being able to witness his everyday challenges, his everyday experiences, his joy for life, his love for being a parent, his appetite to do things that everybody else thought was impossible, resonated and imprinted on me so deeply that I think, as I grew up, nothing was impossible. It was always an option with either a different way in or a different way out. And I think my parents always taught me that I should be ambitious to dream all that's possible.

My mother is also an extraordinary person, and when I was seven years old, they founded and set up Little People of Ireland and still, to this day, run that organization voluntarily. Having access to a community of people who look like me, at all ages and demographics, from seven onwards, probably radicalized me in a way that I wasn't aware of. Being able to have friends where we could talk about what to wear, or boyfriends, or just going to the cinema. What was extraordinary to everybody else was so ordinary to us. Knowing that I could hug somebody who was the same height as me and not have to worry about climbing or having this awkwardness of will they want me to hug them back and I have to ask for permission in order to be tactile with people, you always have to ask permission to be tactile with people just to be clear.

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: But it's easier to invite that when you are hugging somebody else who has dwarfism, for example.

Jillian Curwin: Mmmhmm.

Sinéad Burke: Again, I think of all of those things were key pillars in the person that I've become. But I wasn't in any way aware of the importance of those until I was far older. And I think also just being surrounded by great and good people. My siblings are incredible. I have a really strong network of a close group and a small group of friends. But I think always having the safety net at home to try, try, fail, try again, and again that permission to think that anything could be possible. So when I told my parents that I wanted to be a teacher, they never once translated their fears or nervousness to me as regards to the inaccessibility of a classroom. When I told them that I was interested in fashion, they never dismissed it. They never said that it was facetious. They never said that luxury fashion wasn't open to people who look like me. They just said, “Yeah, great, good.” And were just incredibly supportive in ways in which that I wasn't even obvious of at the time.

Jillian Curwin: I love…I mean, you had touched on like, having your parents create an environment where it was okay to try. I think that is so important. And, you know, it's so interesting and it's like, something I never consider like, the fact that, you know, your dad is someone who grew up, his parents are non-disabled, and here he is now as a parent raising a child who’s having a completely different experience than what he had as a child. But yet you're both little people. That's something that a lot of us will have to face but that’s not necessarily something we talk about. And…I think that does come with an understanding. Like, your dad knows like, what exactly…He's not in your body, but he knows what you're capable of and doesn't, you know, was able to give you these avenues to succeed, whether it was wanting to be a teacher, wanting to go into fashion, and also then helping create this community of little people, which I think growing up I took for granted, what it was, to be able to go to LPA. But then as I grew up and I had to kind of like, step away from it for a minute and, for a couple of years, because like, life was happening and I just didn't want to go and things were going on. But then coming back into it and being around people, getting to make eye contact with people without having to look up at them. Again going back to like, the hugging…

Sinéad Burke: I mean, speak for yourself. I'm the smallest of us always. I’m always looking up.

Jillian Curwin: I'm like right in the middle. I’m like right in the middle…I’m like the baby of the group of like, my circle of friends.

Sinéad Burke: What height are you? This is where we do the comparison.

Jillian Curwin: This is, I'm four feet…I say four feet on a good day, like 3’11”, 4’00”.

Sinéad Burke: I’m 3’5”.

Jillian Curwin: Okay, gotcha. [laughter] There’s that. But there's also like, getting to hug someone and not feeling like that you're, you know, like hugging their butt.

Sinéad Burke: Yup.

Jillian Curwin: Or like, that they have to kneel down because it's, you know, even though if you give them permission, because a lot of time people, people ask if I can hug you, can I like, are you okay if I kneel down or something? And I'm fine with that. But it also does feel like in a way that like though…you’re hugging a child

Sinéad Burke: There's a whole choreography that has to be kind of put in place in order for it to happen. And listen, that's that's the world. But…

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: It's, it's different when you're in those spaces, to your point, being able to be and maintain eye contact with somebody, not needing to lift your head back and take on that strain on your spine, are things that we don't maybe even value or realize until, as you said, you've stepped away for a bit and come back. And, you know, those things have, have always been important to me.

But to your point around my dad, you know, absolutely I think the, the challenges that many people may experience in terms of being parents and being parents with dwarfism, is conversations that we often don't have enough. But I think my dad being a little person also inspired my interest in fashion, probably in the inverse in that, because my dad had lived in his whole body his whole life, and whether it's also being male, though, some men are obviously very interested in fashion, my dad could care less. So I remember coming to him as a teenager because he was the person who solved so many of my problems and saying, “What do I do about this fashion thing? What do I wear?” And he didn't know and didn't care. So I think having him be my, I don't know, focal point of expertise my whole life. And then in this one moment, him being like, “Nah, I know nothing, off you go,” that probably spurred my interest even more because, whether or not I was aware of it, I was looking for answers for him and me at the same time.

Jillian Curwin: Right. And getting into fashion, you know, fashion is an industry that whether, whether you care or whether you don't, it affects everyone. We all get dressed in that, every, in the morning.

So then, you know, I want to ask you like what…You started with, I believe was the blog first, right?

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: What were you initially writing about?

Sinéad Burke: My blog came about as an assignment in college or university. So I was training to be a teacher. My computer ICT lecturer at the time said that as one of the assignments for class, we had to learn how to create a WordPress blog so that as teachers we could have blogs for our classrooms so that when children went home in the evenings, parents could look at the blog, they would have an understanding of the content or the curriculum that was covered that day, and really create that connection between home and school. The lecturer at the time said you can write about anything you want. Now what he meant was within education, but that's not what he said. So I wrote about Cate Blanchett wearing Givenchy couture to the Oscars and why it was really important that we talked about couture as a legal framework and that, you know, it has to be created by hand in an atelier, in Paris, and that is what couture is. And that was my first post. And it became this incredible hub and place for me to record the information that lived in my brain that irritated everybody around me. Because I would sit at the dining room table in the evening and say, What do you think of the news that Alessandro Michele might be the new creative director of a brand that's being resurrected by, you know, Walter Albini? And my parents and my siblings, whom I love dearly, could not care less. They, and I had no friends at the time who cared. They just, they didn't, it wasn't their interest. So I felt really lost and alone. And the Internet became this great place where, because I wasn't writing about myself, because I wasn't putting images of myself into the world, what I was being assessed on was my insight, my language, my writing. And that was such a transformative way in which to build and grow community, despite the ableism that exists in so many people's consciousness. And it just grew and evolved from there out of wanting to have conversations with similarly minded, similarly interested people who I didn't have in my immediate network.

Jillian Curwin: One, if I was at your dinner table, I would have had that conversation with you for hours. Abso…without question. That is so fascinating, it started as just like, this project for… I didn't, I didn't, I knew that you had the blog, that was where you started. I didn't know that it was just a school assignment.

When you talked about Cate Blanchett’s dress like, how did you…Did you frame it around disability yet? Like, were you, were you talking about disability? It was just purely about what is couture?

Sinéad Burke: Yeah. It was, it was rarely about disability because, at least at the beginning years of the blog, the concepts of disability and fashion felt so separate. They felt at such a distance. And it probably wasn't until, maybe…Like, that was 2011. It probably wasn't until maybe 2016 that really the connections between disability and design, and disability and identity and fashion, became much more inextricably linked. And in many ways that came about due to my own personal interest and my own lived experience. So it was less about the disability that existed within the fashion system, but the desire to be part of it.

Jillian Curwin: Right. Because I think, certainly back then, thinking back to 2016, compared to now, there was no disability representation from what I can recall in fashion…

Sinéad Burke: From a very visual perspective I mean, I think there was some in terms of Alexander McQueen was doing some interesting things. There was some great journalists like Lucy Norris working in the space. But in terms of it being a collective, in terms of it being strategic, there was very little representation.

Jillian Curwin: Right. And was it at this time that you were thinking that the blog could be more, something more, could be just a launching pad for something more or was very still like, I just want to talk about this.

Sinéad Burke: Oh, it was totally a hobby. The idea that I have a career and have worked in fashion is, you know, is most surprising to me, regardless of anybody else. It was never you know…I didn't sit there in 2011, 2012 and think this is going to be my career. I fundamentally believed that I was going to be a teacher my whole life.

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: I think what became apparent, I guess, was my ability to build relationships, build relationships deeply, my appetite to learn and to connect with people, and to facilitate conversations that didn't feel amplified enough. I think one of the big transformative moments for me was doing a TED Talk in New York in 2017 called Why Design Should Include Everyone. And that really became this call to action that, on reflection, you know, I think when I look back at that speech, though, thankfully I do not do that too often. What I realize now is I had no answers. All I had was questions. I talked about my lived experience as a disabled woman, particularly as a little person, whether it was in coffee shops, or whether it was in airports, and the challenges that I experience. And I think what surprised me at the time was other people's response to that, that they never thought about it, or were aware of it, or just, it was so far removed from their own imagination. And I look back now thinking, gosh, all I left that audience with was questions. I gave them those solutions because I didn't have any at the time. I didn't know enough. I'm continuously learning. But that really felt like such a key moment where it was this Venn diagram of both my interests, my lived experiences, and my ambitions to really professionalize myself and see that there might be an opportunity to build somewhat of a career in this space.

Jillian Curwin: So then how did you do it? Where, like…? Where did you then start with building this career in fashion?

Sinéad Burke: So from TED, I got a phone call from Imran Ahmed, who was at the Business of Fashion, is the editor in chief and founder of the Business of Fashion. And he had seen the TED Talk and he called me and said, “Do you know anything about fashion?” And I said, “Do I?” And then talked at him for an immeasurable amount of time on the phone about my interests between fashion, design and accessibility. He invited me to come and speak at the Business of Fashion Voices Conference in 2018. I stood on stage in altered Burberry, due to a connection and a relationship that I had, a woman named Alice Delahunt who was working at Burberry at the time, and stood on stage in the UK in front of some of the most senior and prolific people within the fashion system, and shared with them an evolvement of the TED Talk, but much more specific to the fashion and design industry based on my own exposure, interest, and education. Because even today I sit and read WWD, The Financial Times, The New York Times, Vogue Business every morning and had absorbed a huge amount. And having that visibility to the industry, and for the first time being able to be in dialogue with key stakeholders at all levels, was incredibly transformative in building that network to be able to put forward suggestions, ideas, to move the dial and begin to build, not just a career, but also hopefully respect, expertise and solutions as to what the industry needed.

But I was, I suppose, far braver then. There was far less risk. I was this unknown. I was standing on stage. I was telling all sorts of companies what they should do and, over time, and I think you'll know this as well Jillian, when you’re trying to create change in an industry that is so impenetrable, it really takes time to build those relationships, to earn trust and to create change.

Jillian Curwin: Absolutely. I think, you know, the fashion industry it's, it's an interesting paradox, I think, within it because it's one where, literally every season we're asking what's next, what's new, what haven't we seen before. We're challenging designers to think outside the box, to do something different. And yet, at the same time, what we see on the runways, or what we're expecting to see on the runways in terms of the bodies that we're designing for we’re still expecting it to stay in a very limited box, that has gotten, that has expanded over the years. But there's still this expectation or this like, I don't know if like, expectations the right word, but like, the stubbornness to really design for other bodies…types that are different, that are disabled particularly. I think it's definitely changed with other movements that have had them. But I think with disability and, and you can correct me if I'm wrong, because obviously you're much more on the inside like, there’s this is like, hesitancy because…One, because our community is so diverse, we can't design for every disability all at once. That's not going to happen. But also it's thinking like, well, you know, like disability just is not in fashion. It's, it's never been seen, again like, going back to like just the stigma of it. It's never been seen as cool.

Sinéad Burke: You know it’s, it's interesting. I think if I reflect back to when I did the Business of Fashion Voices in 2018, if somebody had have asked me then, which they have done what I thought success was within the fashion system, my answer at the time would have been adaptive product and greater representation on the runway. Several years later, and I think initially since founding Tilting the Lens in particular, my answer to that question has changed, and in many ways broadened. When I think about visibility and representation within the fashion system now, yes, what is on the runway is of vital importance. But actually I think it's also about the boardroom. I think it's also about the senior suite of leaders within an organization. I think it's the interns. I think it's the people who get their first job at a college, or out of an education program that might not be at university level. I think it's about the suppliers who that organization engages with. I think it's about the staff who work in retail units. For me, I think my interest and my investment in the fashion system has become less about product, though it is important, and more about the system, particularly from a business perspective, because I have learned that if we only ever focus on product and output rather than process, it may not always impact the demographics of the organization, that they may assume that they can design for us rather than with us or by us.

Jillian Curwin: That is so true, and I feel like I now need to revamp my whole approach in thinking about this because I think, and I think it just comes from a lot of it when we talk about because I have always kind of been like we need to be designed for because, and I think it's just because for so long we've never been included in the conversations, whether as a target demographic and from a business perspective, that truly doesn't make sense because disabled people are the world's largest minority, we’re, you know, in theory we should be designed for just be…like, by the numbers. Like, if you design for us, we will shop for you, from you. But yeah, the thought of like, kind of looking at the system I think is something that even with what's happening now and with other groups, it's like that's still, like, that's I think really what we need to be talking about because, you know, the saying of the disabled community’s nothing about us without us. And it's, I think, as a whole we need to kind of stop saying just design for us and start saying no, we want to see from the interns all the way up to the C-suite disability representation.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: Not saying that there might not be with, in terms of invisible representation, but we need to see it.

Sinéad Burke: But we also need to foster cultures of belonging and psychological safety where…

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: If and when there is representation of invisible disabilities that people feel safe to self-identify, that people have their access accommodations considered and implemented, and that we are investing in this strategic priority. I think for me one of the challenges when it comes to product is that we often rely on the business case as a way in which to validate the need for product. And while it is important to acknowledge that, you know, there is somewhere between 1.9 trillion US dollars in terms of the discretionary spending power of disabled people, I think it's of vital importance to also acknowledge that 50 to 75% of disabled people are unemployed or outside of want.

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: And I think if we are only ever relying on that 1.9 trillion to convince business leaders of the need to design for us, the challenge therein comes one, if the product is incredibly unaffordable. It means that the organization will only ever design for us once…

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: Because it won't be profitable, because they also haven't built relationships with community, they also haven't undertaken meaningful collaboration in terms of the design process. But I think it undermines the need for us to look to this as an employment issue, which will in turn begin to address some of the challenges that exist around access to health care, access to independent living, for example. Many of those barriers will remain. But I really do believe that we only ever look to this as product, we are creating expectations of the disabled community that they must transact at whatever cost.

Jillian Curwin: Right. And that's…I am like, ashamed to say that I never thought of it from that lens before. And I think because here it is so much of like, we just need the adaptive products, we need to see the visibility on the runways, and, and I think that's what you're doing with Tilting the Lens, which I want to get to. It’s, it is so much more and I think we need to be thinking about that. And speaking, you know, like, and I said this recently with people, speaking for myself, I'm working in an environment that my parents worked in, that I grew up visiting them in the office, and I never saw myself there.

Sinéad Burke: Mmmhmm.

Jillian Curwin: I never, and like, even now I'm dealing…because I'm the only, as far as I know, I'm the first little person to be working there. That's what I was told. I wouldn't be surprised if that wasn't true. But as far as I'm the only visibly disabled person in my office, and there are so many times, and it's interesting how fashion plays into it, the more professional I dress that day, when I see myself in the mirror, when I see myself in a reflection, it's this imposter syndrome of “You look like a child. You don't look like you belong here. You look like you're a kid playing dress up.” And it's not because of the clothes I'm wearing, but it's because of the fact that, until me, I didn't see anyone like me. And that I think, is something that, for a lot of industries, we don't see disabled people, not just fashion. And I think that's something you're addressing with Tilting the Lens. And that's something I think as a whole we need to be, when we talk about representation, we need to be thinking about it's not just that visibility on the runways or in the magazines. Not that that's important…

Sinéad Burke: No.

Jillian Curwin: Because we're not talking about that in a second. But…

Sinéad Burke: But it’s broader. You know, if we want representation on the runways, the runways have to be in buildings or spaces that are accessible.

Jillian Curwin: Mmmhmm.

Sinéad Burke: The casting directors have to be mindful of access needs. The creative director has to be looking at this as a priority, which means the CEO has to provide the financial investment for it to be an accessible building.

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: It's multi-layered, and I think sometimes we are not focused on the nuance because you can also get lost in the nuance, then nothing is achieved. But I think there is a desire to simplify a complex problem, and the complex challenge takes time, collaboration, so many conversations, and the reality is we'll be trying to solve it for our whole lives.

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: And that's both the opportunity and the burden.

Jillian Curwin: That is true. That is so true. And I think, you know, it'll be happening after, for generations after us. It was happening for generations before us. So it's…this is it new people.

Let's talk Tilting the Lens.

Sinéad Burke: Sure.

Jillian Curwin: Where did you, where did that come from?

Sinéad Burke: So Tilting the Lens was founded/registered on the 15th of October 2020, which was the same day in which I released a children's book called Break the Mold, which probably will give you a sense of my psychological mindset in the midst of a pandemic wherein I published a children's book, it got on shelves, and immediately set up a company. But in reality, the company didn't begin or fully exist until around the first quarter of 2021. I think the pandemic was instructive for a lot of us, particularly those of us who identify and are part of the disabled community. Being at home, being in one place made me at least incredibly reflective, and gave me time to be both generous with myself and critical. I think I had set myself an ambition to participate in the luxury fashion industry in the hope to create change. And yet, when I open the doors of my wardrobe, I have some of the most beautiful custom clothes in existence. But they are for me and only me. While it proves that some of the luxury brands in the world can do this, they have allowed me to be the exception and not the rule. It provoked me to ask the question “Did the fashion industry become more accessible because I was part of it? Or did it become more accessible for me?”

At the same time, while we all had greater proximity to disability because we experienced COVID, if you look to the stats in the UK for example, six out of ten people who died of COVID-19 in the first part of the pandemic were disabled. We created a lexicon to become less sensitized to the death of disabled people by, when a number was announced, of the number of disabled, the number of people who died, we would immediately ask, “Yes, but were they vulnerable? But did they have underlying conditions?” as if their loss was more palatable to us because well, they were kind of broken anyway, which is so hard to say.

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: Never mind acknowledge that that was the reality. So while this was happening and the internal monologue was being more critical, it made me acknowledge the fact that systemic change is not possible with an individual but requires a collective. So setting up Tilting the Lens was an aspiration to build almost an engine that could root itself and embed itself in an organization, fashion and beyond, rooted in the pillars of education, advocacy and design. And to build a team, a majority led disability team, that would provide organizations with a roadmap and a blueprint. Because so often what I experience from leaders or people and companies is “We really want to do this. We just don't know how. Where do we start? We feel overwhelmed.”

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: And then simultaneously to be a connector between community and corporate. I was very aware of that, in terms of my career in fashion, I had built up currency and a network and positioning. And how could I utilize them, not just for myself, but for the community as a whole? So being able to, through our work, connect people quietly, and very publicly, for opportunities, for learning, and to be a facilitator for that interaction has been the greatest privilege of my career.

Jillian Curwin: And it’s been absolutely amazing to watch. And I don't know if I've actually ever told you this. I know I've talked about it, and I certainly wrote about it in my, in one of my initial posts is that I started Always Looking Up, it was a blog and the blog is still active. It's just kind of dormant at the moment while I've been growing the podcast. But I started…I had the idea for it in, around, I guess it must have been August 2019 because that September, Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex, edited the September issue.

Sinéad Burke: Mmmhmm.

Jillian Curwin: And you were on the cover.

Sinéad Burke: Mmmhmm.

Jillian Curwin: And I happened to be in Europe at the time for a wedding. So I was in, I was in Holland. I literally went to every single newsstand I could find to find this magazine, to find this issue. I was going to own this if it was…I didn't care if I missed the wedding, I was going own this issue of British Vogue when I knew that you're going to be on the cover, because it was like the first time that I was like, “Oh, I'm seen. Oh, I can be on the cover. Oh, dwarfism can be on the cover of a magazine.” Like, and then so because of that, I was like, okay. And it's like, and I'm like, this is what I want to be doing. I've always talked about fashion. I've always complained that I'm not designed for in this industry. Like, so that's kind of like where Always Looking Up came from is like, I want to be doing some, play some small part in this. So for that I want to say thank you.

Sinéad Burke: What an honor. Thank you for sharing that story with me. I like, I've red cheeks sitting over here. But, but thank you. And, and I'm so glad. Look at what an incredible thing it has borne made happen.

Jillian Curwin: And it's been amazing to…thank you. And it's been amazing to watch over the past two years what you've, three years at this point. No, I can do…four? Close enough. What you've done since with building Tilting the Lens, with, and you know, I saw like you were working with NASA. And like, and I think it's so many, it's so…and like seeing the work that you're doing is something that I didn't think, again kindof going back, I didn't think about. It's like, there's so many other areas in this, in the world, so many industries, where disability is represented, represent…, represented and, you know, how like, thinking back to my younger self, it's like if I saw myself in some of these industries, I wouldn't have given up on those dreams. So now how many people, how many…the next generation are growing up and seeing themselves in industries because of the work that you're doing? And it's not just limited to fashion. I think, in terms of accessibility, it covers all areas.

Sinéad Burke: For us, you know, we really look to design as one of our principles because, and we talked about this earlier, you know, we're disabled by design.

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: We're disabled by the design of the built environment, by the design of people's mindsets, of behaviors. And actually, if we can transform that, that is the way in which we create, hopefully, a more equitable future. But the idea that design is multi-format, multi industry, so starting in the fashion industry and then moving further afield, also allows us to position accessibility as something that is beautiful and/or design-led. But thank you.

I mean, it was an incredible honor to be part of the forces of change issue of British Vogue, particularly with the Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle. I will say that my experience on set, in that moment, was probably not as accessible as it could have been.

Jillian Curwin: Mmmhmm.

Sinéad Burke: But I remember receiving the Guinness World Record for being the first little person to be on the cover of any Vogue magazine ever. And on receipt of it, I had this mixed emotion of feeling a great sense of pride, a sense of guilt, and a sense of embarrassment. Right? So much of what has been possible for me is due to timing, whether it's generational, whether it's where the world is at in the moment and the time in which I live, the skills that I have, the privileges that I have. But simultaneously why did it take until 2019 for the first little person ever to be on the cover of a magazine? And in many ways I made a quiet commitment to myself, that if I ever had the opportunity to widen the lens or the aperture in which more disabled people could be seen, could be witnessed, could feel a sense of pride over who they are and their bodies and their minds and how they experience the world, that I would do everything I can to make that happen, never knowing, of course, what would unfold in the future.

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: But I think I have always been ambitious to ensure that it is not just I who gets to be a success, but I get to leverage that positioning to hopefully give visibility and opportunity to as many different people as possible.

Jillian Curwin: I love that and I think…I didn't know about what happened on set in 2019, but reading about, and then want to talk about, the May issue of British Vogue, the 2023 issue of British Vogue, and reading about that and seeing like, what you've, what you were able to because of Tilting the Lens, because of your work, were able to create then, going back to British Vogue, kind of not necessarily where it started, but certainly where, you know, like kind of coming full circle.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: So where did the idea come from to do the disability issue?

Sinéad Burke: It came from Edward Enninful, who's the editor in chief of British Vogue. So he emailed me last June and said, “Hey, do you have time for a call this week? We'd love to talk to you about an idea,” which, by this date I should know, is a sign that your life is about to change, but still it came as a surprise to me. And the team and I had a call and they said that they had an interest in doing, kind of, a disability focused issue. They wanted to move the dial on accessibility but didn't know how. And felt that through observing the growth and progress of Tilting the Lens that actually they could, and we could be a partner for them. What I really admired was A, their vulnerability. I think it's very difficult, but so important when you're in leadership, to acknowledge that what we do and don't know. And I think, I also admire that when we talk about co-design, whether it's in product or whether it's in process, often we only bring disabled people in at the end, and get them to audit or give feedback that there's no possibility of it actually being implemented. Whereas what I really liked was we were invited into the room in which decisions were made and were equal stakeholders in supporting and shaping those decisions. And it started with us supporting with providing a list of potential talent who could be in the magazine, who could be writers, who could be creating online content. Of course, that first iteration of that list was enormous, and we had to whittle it down.

Jillian Curwin: I'm sure.

Sinéad Burke: I had some suggestions. We had some suggestions. We often met in the middle. We debated, we challenge, we, you know, put it in place, and then we had to think about…Okay, so we have this ambition to create beautiful imagery of disabled people who have a spectrum access requirements and identities, while also having a crew, who also have access requirements, for both visible and invisible disabilities. What does the space need to look like or be? We audited every studio in London to get a sense of what meaningful accessibility look like for those variety of access requirements. And as you might imagine, we were only left with one studio. So even trying to ensure that we had access to that studio for the treat…for the three days that we shot images was a real challenge.

We then undertook, simultaneous to that, digital accessibility training for the whole British Vogue team, to support them in their personal and professional understanding around alt. text, captioning, audio description. We were on set for each of those days, the whole Tilting the Lens team, at different points, to be able to support people and to be able to just create a disability first experience. That if they needed to have conversations, if they needed to have access considerations, that there was somebody there with a lived experience and understanding to be able to support them.

On set we had a quiet room. We ensured that catering was accessible. We had changing room facilities that supported people, whether it was based on gender or whether it was based on just overall requirement. We ensured that on-set was a safe space. There was a couple of people who had trauma-informed experiences who really needed and required a one gender dominant set for their own safety and comfort. We ensured that that happened. And really just thinking about that from a multidisciplinary perspective. And then once we began to put in place the issue, we supported with access to suppliers, whether it's the Royal National Institute of the Blind, whether it is the Deaf and Disabled People in Television, which is a UK based organization to support behind the scenes and production talent. We supported with language and copy, changing language from disabled and non-disabled and putting that in place. It was as broad as you might imagine. We supported Frances Ryan and Selma Blair being…and Lottie Jackson being the writers for some of the issue. We put together a whole list of talent who've written online content, and really just trying to leave British Vogue with a database of extraordinary people who can support them, whether it's sign language, interpreters, close captions, or just future talent that they can engage with forevermore. It is a project that we are really proud of in some ways because it lived in our inboxes, and on Zoom calls, and in meetings and photos for such a long time it kind of didn't feel real. And now that it continues to be on shelves, and it is something that we can witness. I came in from Paris yesterday on the Eurostar, and it was just there in every carriage. There was like, three or four copies for people to just openly read. And I was like, “We did that.” And tomorrow all of the Tilting the Lens team come to London to actually have a moment to celebrate…

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: Because it was such a huge amount of work. We were all stretched. It required so much of us personally, professionally, in terms of time. We worked late hours. We really tried to give it our all. And this issue cannot be representative of everyone, nor should one issue be. It will never be accessible enough, though it is more accessible than previous. But actually as a leader of a team, being able to create a moment deliberately where everybody comes together and we get to just reflect and celebrate what we've achieved so far, I'm really looking forward to it.

Jillian Curwin: As it…that celebration better be long through the night because you guys absolutely deserve it. This issue is stunning. It is brilliant. And like you said, like, you made it accessible in ways that British Vogue hasn't been before. The fact that you did an issue that is in Braille so that way those who can't see, who are blind or visually impaired, can still read it and access this issue, which is like…yes. Like why…? And it's also like, you know, it's like why…we don't necessarily think about the fact that like, people who can't see can’t then access these magazines.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: And…

Sinéad Burke: It also probably questions like, should we make the advertising available in Braille? Or should it just be the text? And I was like, it's a fashion magazine. We should absolutely make the advertising available in Braille because knowing that a Tiffany campaign is in Braille, for example, just creates new customers, new potential employees. But it's also about equity of experience.

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: That we shouldn't just make the content pages in Braille because Vogue is far more than that. So it was a continuous dialog.

Jillian Curwin: Right. And I remember the day it dropped on social media. This is recent because this is the May issue. I have never seen, and one thing I learned with the disability community, and I didn't really come into the disability community until I moved to New York a couple of years ago, is how we celebrate each other, how we share each other's successes. So the day this dropped of all social…when all the images dropped, I couldn't, andI'm saying this in the best way possible, I could not escape it. I've never seen disability celebrated so much. And then by people who are not disabled, who are not part of the community, but were like, this is amazing. This is, this is incredible what this issue is doing. And…

Sinéad Burke: But it, it's so funny that that was your experience of that day. That day I was here, actually, in this room in London. I had like, two colleagues over here. I had others at home. We had this WhatsApp group, you know, it was like, almost we were like, in battle. Everything was timed given what was happening. My heart was like, beating out of my chest, my breath, I, I couldn't look at the Internet. I was just like, we have to, you know…

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: It was such an amazing process. But the first time it felt really real. And, you know, I think we were genuinely very nervous about how the community would respond. We had, with great intentionality, tried our very best for it to be as good as it could be with the resources that we had within that moment. It's absolutely fair that not everybody will like it, nor should they.

Jillian Curwin: Mmmhmm.

Sinéad Burke: Everybody has individual taste. But I think the response to the issue, both on social media and people picking up and people talking about it, has been truly phenomenal. And I don't have the data on what that actually looks like, but I really want to have access to it and it was just incredible. Still now hearing people's stories, receiving notes and DMs, people talking about their different experiences because of it, has been truly extraordinary.

Jillian Curwin: I’m sure. I mean, it's something truly to be celebratory of, and proud of. For me personally, but then like, for the disabled community as a whole, I think we're all, for the most part, like you said, there are going to be people who are going to say, well, this isn't enough, and it's…

Sinéad Burke: It’s not.

Jillian Curwin: One issue is not enough.

Sinéad Burke: No.

Jillian Curwin: One issue is not enough. But, again, like you said, going back to you being on the cover, it's taken so long for the industry to kind of catch up. And we do have to recognize that things, things do…I think I was talking to you, or trying to initiate this conversation with you. I think when you were like, about to launch it.

Sinéad Burke: Oh yeah.

Jillian Curwin: You said you were in the middle of a years long project.

Sinéad Burke: I was like, “Jillian, let’s not do it this week. That would be great because I'm going grey and, you know, it's pretty stressful.” And also the thing that, you know, we, we couldn't talk about it. We were doing something the following weekend in Ireland and we had to change the dates because I had to be at London for press. And we had to send this email, we're like, “So we're launching this project that we cannot tell you anything about.”

Jillian Curwin: Right.

Sinéad Burke: “But unfortunately we're going to have to move the thing that we have committed to because of this. So please just be cool and allow us to do it. While we can't tell you anything, but please trust us. If it was possible to not change as we would.” And actually, you know, we're so grateful to everybody around all of those moments for giving us the flexibility while we…

Jillian Curwin: Yeah.

Sinéad Burke: Figure out how to do something that we've never done before.

Jillian Curwin: And I mean, the work, it shows. It's, again, I've said it, it's brilliant. It's stunning.

Sinéad Burke: Thank you.

Jillian Curwin: As a disabled person, as a little person, I'm incredibly proud to see this because again, it's just, it goes back to representation…

Sinéad Burke: Yeah.

Jillian Curwin: Of seeing disability as something beautiful and to saying like, this is, this is a starting point is it's all just a start point.

Sinéad Burke: It’s not a destination.

Jillian Curwin: No.

So, I have two questions for you. They’re, they’re are similar. If your younger self could see you now…

Sinéad Burke: Yes.

Jillian Curwin: What do you think she would say, think, believe, about who you've become?

Sinéad Burke: I think she would be very proud of my personal growth. I talked a little bit already about the fact that I am in therapy. I go to therapy every week and I've been in therapy for about two years. And I think often as disabled women, and disabled people generally, we can be so focused on one aspect of our disability that we're also, say, not mindful of our anxiety, or our mental health, or mental illness and being able to unpick some of my own behaviors and pick some of the ableism and that lives within me, and have more grace with myself and with others, and learn more about myself and why I am who I am. I hope that she would be proud of me for that, though I'm not sure a five year old would understand the complexity of that. I think my younger self would be surprised with the way in which my life has unfolded, surprised in the sense that it was possible, not necessarily that I did it. I think from the youngest of ages I have always been strategic and ambitious. I have always been very driven and known what I wanted. The unknown has always been whether or not the world would let me. And I think younger me would probably caution me to be gentler with myself. I am very proud to lead an extraordinary team. We are mostly based in Europe, but our client base is international, which means I travel a lot, which means the rate at which we work is quite fast, particularly as a start-up company. I think my younger self would tell me to be more mindful of bringing joy into my life and making sure that the world does not pass me by, because I am going at such a rate of knots.

Jillian Curwin: That is so profound and so beautiful. And I think that's, to feel reflected in your growth like that is so important. And I think she would be incredibly proud of you.

Sinéad Burke: I hope so.

Jillian Curwin: I think she is.

And then the second question, kind of on the opposite, is looking ahead, where do you see yourself in the future? Whether that's purely focused, looking at through Tilting the Lens or for you personally, where do you see yourself?

Sinéad Burke: Ummm, I've just bought a house. It will be my first time to move out of home. I have been very lucky to live with my parents for such a long time. Some of that is due to a lack of financial independence, some of that is due to a lack of accessibility in rented properties. Where I see in the future as having dinner parties. Where I see myself in the future is creating this nest and safe space for myself, my loved ones and my friends to gather and, I don't know, share books, and share ideas, and share thoughts, and share emotions and tears and all of those things. So very personally that's hopefully where I see myself, though I have not yet schedule time to pack boxes or to figure out what kind of floors, or blinds, or dishwasher. I want all of these things that are far too complex for me currently to understand that I now have to figure out.

Where do I see myself professionally in the future? I would love to see the company continue to have an impact in quiet and in more vocal ways. I would love for my team to respect me as a leader that deserves their respect, and that is one that fosters a culture where people feel safe, and feel empowered, and feel creative. I would love for them to feel similarly, that I respect them and that I admire them, and that I learn from them always. I would love to be a person who leaves people feeling better about themselves and their day, and that people feel more qualified to engage in these conversations, to deliver this work, and to feel like they can actively make a difference themselves. Yeah, that's what I hope.

Jillian Curwin: I think it's going to happen. I'm very excited to continue watching and seeing what comes next with you, with Tilting the Lens, and just kind of like with this industry and with this world. I think there's so much more that needs to be done and there's people like you and companies like Tilting the Lens that are doing the work. And I'm excited to see, you know, looking ahead the next month, months, years from now, I'm excited to see what the future is going to look like.

Sinéad Burke: Thank you. And, you know, I think platforms like this are so important Jillian. And I hope that you get to take time, not just on this, your 100th episode, which is such a monumental feat. Like, can we, like, a centenary of episodes is extraordinary. Like, even to do that once a week is two years worth of work, which is far more than what this is. And I think, yeah. It's the rising tide lifts all boats. It is always about collaboration, not competition. And I think the more of us that are in this space, the more of us that are interested in creating change, the more likely it is to happen. So I hope that you can also take a moment today and celebrate yourself, your team, and the many people who make this happen.

Jillian Curwin: I will. And my brother who's listening and is going to be editing this episode, this, I want to give him a shout out because this podcast would not exist without him, because I do not know how to do the technical things that he does. I just do the conversating, the outreach, the promotion. But like, anything editing wise, that's all him. So…

Sinéad Burke: There's no just. You do a lot, as does he.

Jillian Curwin: Yes.

Sinéad Burke: You do a lot.

Jillian Curwin: He does. He does all the technical stuff so I want to give him a shout out and just…I'm very excited to see who we get for the next 100 episodes in two years and see…

Sinéad Burke: Absolutely.

Jillian Curwin: It's all very exciting.

Sinéad Burke: But thank you so much to me on this program and for having me…

Jillian Curwin: Of course.

Sinéad Burke: And just, for such an important conversation that often, as disabled women, we only get to have behind closed doors. So I'm really excited to see what other people's responses is, and whether or not they agree with us or completely disagree.

Jillian Curwin: Yes. And if you agree or completely disagree, I want to know. So please let us, let us know. And if you really disagree and want to come on and talk to me about it, let's do it. Let's have, you know, be a part of the next 100 episodes.

Who do you look up to?

Sinéad Burke: I mean, the actual answer is everybody. Because as we've discussed, I'm three foot five, so there's very few people in the world that I physically do not not look up to, which is the joy and the challenge of being often the smallest person with achondroplasia in the room, regardless of age.

Who do I look up to? So many people. I look up to people who are kind in a way that is not performative, but in a way that is often rooted in generous, conscious acts that are undertaken without need or desire for exhibition. I admire people who are thoughtful. I look up to people who are vulnerable and look to that as a strength and not a weakness. I look up to people who are smart, not in a way that is defined by intelligence, but people who have an emotional intelligence or an interest in the world and a curiosity in people. I admire people who are loving, which is language that I was not always familiar with or comfortable talking about, but people who love themselves, even on their challenging days, and people who are gracious with their love of others. I look up to people who make me see the world from a different perspective and who challenge me constructively and do tell me that I talk nonsense or have not got a clue what I'm doing sometimes. Because being surrounded by people who challenge you is honestly one of the most important things, but also one of the most loving things that you can do with somebody. If we all agreed, life would be so terribly dull and boring. And so those are the people I look up to.

Jillian Curwin: That is so true. That is such a beautiful answer.

Are there any questions I have not asked throughout our conversation that you would like to answer at this time or anything else you want to say? Final thoughts?

Sinéad Burke: I feel like you have grilled me appropriately in the best possible way.

Jillian Curwin: Thank you. Thank you very much. And now I want to give you the opportunity to plug yourself. Let my listeners where can they follow you, where can they follow, Tilting the Lens, where they can, where can they see all the work you're doing.

Sinéad Burke: Sure. So my name is Sinéad Burke. You can find me on most social platforms. My username on most of them is @thesineadburke. But if you want to learn more about Tilting the Lens, you are best to go to our website www.tiltingthelens.com, which is also the place in which we often put job opportunities, or webinars, or events that we are doing and undertaking if you ever want to participate in them. If you have any questions or want to know more about the work that we do or how we connect community to corporate clients, please feel free to email us at team@tiltingthelens.com and that will reach us and we will be able to answer those questions, or support, or add to our databases, or our newsletter. But we are @tiltingthelens on most platforms and, like Jillian, always welcome a dialogue and conversation.

Jillian Curwin: Yes, and I will have links to follow and links to the website, links to contact, both in the show notes and on the transcription page that will be on my website. So go check that out.

Sinéad It has been absolutely wonderful talking with you. I have a little icebreaker, but at the end, that I like to do with all my guests, where I have five categories and I just wanna hear your favorite and each one.

Sinéad Burke: Sure.

Jillian Curwin: Favorite book.

Sinéad Burke: A book called Thick by Tressie McMillan Cotton.

Jillian Curwin: Favorite TV show.

Sinéad Burke: Ever?

Jillian Curwin: However you choose to interpret that, ever, right now.

Sinéad Burke: Derry Girls.

Jillian Curwin: We're going to talk later. I have so many thoughts and love for Derry Girls.

Okay. Favorite drink.

Sinéad Burke: Diet Coke.

Jillian Curwin: Favorite fun fact that you know.

Sinéad Burke: Like generally? Or about myself?

Jillian Curwin: Generally, about yourself. Again, however you choose to interpret that.

Sinéad Burke: Favorite fun fact about me is I can lick my elbow. But that's actually not interesting on this podcast because, I think, everybody with achondroplasia can make lick their elbows. It's only interesting outside of rooms like this. My general fun fact…

Jillian Curwin: Wait, we could…Wait, wait, wait, we could do that?

Sinéad Burke: Can you lick your elbow now?

Jillian Curwin: I don’t think so.

Sinéad Burke: Try. Close…see? Allegedly it's a physical impossibility for one to be able to lick the robot, but I think people with achondroplasia can. See? Gross.

Jillian Curwin: My jaw’s dropped.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah, but apparently people with achondroplasia can, but allegedly nobody else can.

Jillian Curwin: I learned something new.

Sinéad Burke: Yeah. So that's my fun fact.

Jillian Curwin: I thought that is the best fun fact ever.

And last one, favorite piece of advice you've ever received.

Sinéad Burke: If somebody chooses to be unkind to you because of something which you did not control, nor make a choice about, that says everything about them and nothing about you, which is advice my mother gave me when I was very, very young and really struggled with people who made fun of me because I was a little person. And she used to say, “You didn't choose to be a little person, but they are choosing to make you feel less and that is on them and not you.”

Jillian Curwin: That is a perfect note to end on. Again, thank you so much for coming out. Thank you for being, for being here for my 100th episode. It is an honor to have you on and to talk to you, and the doors open for you to come back.

Sinéad Burke: Any time.

Jillian Curwin: Whenever you like whenever there's something,...I'm sure there is so much more to talk about.

Just this final, final thing I just have to ask of you is to, for you to remind my listeners in your most fierce, must badass voice possible that height is just a number, not a limit.

Sinéad Burke: You want me to say it?

Jillian Curwin: Yes please.

Sinéad Burke: Okay. Height is just a number, not a limit.

Jillian Curwin: Always Looking Up is hosted by Jillian Curwin and edited and produced by Ben Curwin. Please make sure to rate, review, and subscribe and follow on Spotify so that you never miss an episode. Follow me on Instagram @jill_ilana and the podcast at @alwayslookingup.podcast for updates and check out my blog JillianIlana.com for more content about what it is like to be a little person in an average sized world.

Thanks for listening. See you next week.