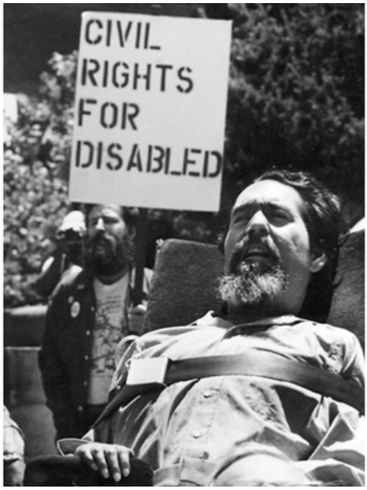

ADA Turns 30

Yesterday marked the 30th anniversary of President George H.W. Bush signing the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) into law. The ADA was the first comprehensive civil rights law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability. To mark the occasion I had a conversation with Bekah Bailey, a fellow little person and disability rights advocate. We discussed the impact of the ADA, the history and status of the disability rights movement, and our hopes for the future.

Jillian: Tell me a little bit about yourself- how did you get started in advocacy.

Bekah: I guess my start into advocacy probably began in late high school, early college. It was me being at the intersection of me being queer and disabled that forced me into advocacy. It was part of my life because of that. I would define the beginning of my career in activism and advocacy back in 2017 when they started making cuts and changes to the ACA (Affordable Care Act). I posted something on Facebook, a link that someone else had written, and I posted something personal along with it. Someone reached out to me and said, “We are gathering folks from all over the country. If you can be in D.C. this weekend, let us know.” Eight hours later I was at the airport heading to D.C.

Jillian: That’s amazing.

Bekah: It was very wild. It all just happened so fast. I definitely don’t think I thought about it until I was home again. We went out there and we were at the Capitol, in the Senate building, lobbying to legislators, explaining why it’s important. That was what spearheaded me into my grad program, from which I recently graduated, as well as the career path I’m looking at now.

Jillian: What grad program did you do?

Bekah: I just got my Master’s in leadership and advocacy.

Jillian: Congratulations. And do you know what you want to do with it?

Bekah: So, my undergrad is in stage management and the master’s is in advocacy and political leadership. I, right now, am campaign managing. I found that stage managing and campaign managing were fairly similar. I don’t know if that’s specifically what I want to keep doing but something involved in legislative processes and continuing advocacy on a more legislative side is something that I think I really want to pursue.

Jillian: Very cool. Do you feel that when you were growing up, and now as an adult, that having a disability limits you? Or, do you feel that society and the environment limit you as well?

Bekah: Yeah. So, I’m second generation achon (achondroplasia- the most common form of dwarfism), both of my parents are achon and my sister is as well. My mom, after our father passed, and we were both really young, was the sole parent for the majority of my life. She laid it out as facts: we knew at a very young age that things were not made accessible for us. It wasn’t going to be easy and it also wasn’t going to be something that we could use to excuse ourselves from being involved or invested. She really instilled at a young age that we’re still going to do what we need or want to do and you just gotta figure it out because the world won’t for you. It was easy, when you’re younger, to pass it on as a problem because I’m this way. That can be a viewpoint that’s helpful to people because it’s less nuanced. It’s easier to explain it that way. As you get older and you understand the systems and the society that we live in, it’s clearly the society that wasn’t and isn’t being built for us. We’ve grown past the idea that it is our own problem that we need to handle within our own being. It’s outside of us where the problem has to be fixed.

Jillian: Right. In school, for me, I had a 504, I had those protections. But, my teachers didn’t know and if I didn’t say anything, I wouldn’t have gotten the accommodations I required. Was that the case for you? Did your teachers know ahead of time or did you have to fight for what they were required to give you?

Bekah: There wasn’t much of a fight ever. It was very different between myself and, for example, my friend who is also an LP. I had a 504, and for the first few years of elementary school she had a *504 but also an IEP. She was a lot more reserved and quiet so she didn’t speak out for herself when she was younger. So, without reaching out, things wouldn’t have been accessible to her and she wouldn’t say anything about it. I think, with my experience, I was definitely more outspoken. I don’t think I can pinpoint not having access for me but I know I could pinpoint it for my her. There were definitely moments where things weren’t being accommodated to her- whether it was because she didn’t say anything and the teachers didn’t know or the teachers knew but she didn’t say anything so the teachers chose not to [make accommodations].

*504 Plan- a plan developed to ensure that a child who has a disability identified under the law and is attending an elementary or secondary educational institution receives accommodations that will ensure their academic success and access to the learning environment.

*Individualized Educational Plan (IEP)- a plan or program developed to ensure that a child who has a disability identified under the law and is attending an elementary or secondary educational institution receives specialized instruction and related services.

Jillian: Do you feel protected under the ADA? If there is something that needs to be changed, or accommodations that need to be made, do you feel like the law protects you?

Bekah: I think so. I think there’s so many loopholes around it that, at some point, I have to ask “What’s the point of the ADA if people are just going to get around it?” I think, in its intentions, I’m protected but, again going back to society, everybody’s found loopholes for anything so that they don’t have to do more work. Moreso now, the ADA could protect me if we could stop these loopholes and if we could stop the roundabout ways to get out of it.

Jillian: As it’s written now, do you think it’s effective?

Bekah: I think it’s definitely outdated. Obviously 30 years ago society looked different than it does now. There’s basics to society that it was helpful then and it is helpful now. But, I think even just looking at how technology has grown in the last five years there’s definitely opportunity for edits and updating it that would be beneficial to disabled folks.

Jillian: Did you learn about the disability rights movement in school?

Bekah: No.

Jillian: Me neither.

Bekah: I think the movement itself, I probably didn’t know about until college, when I did personal research. In public school, definitely not, there was no discussion of it all.

Jillian: Why do you think that is?

Bekah: I think...If we look at it, it’s still the same problems that should be in the textbook because they happened so many years ago, are still ongoing. And you could easily say that for any marginalized group right now. I think disability in itself, it could be this, it could be that, and I think there’s definitely a fear in talking about disability when you’re not a disabled person. It’s an unknown territory that you don’t, of course, want to bring up in the wrong ways. But, I think that has gotten to the point where they don’t bring it up at all for that reason which is, I think, more detrimental than bringing it up and maybe being a little bit wrong or a little bit off-color when you talk about it.

Jillian: Agreed. I think that people don’t understand and they also don’t realize that disability doesn’t discriminate, that anyone can suddenly have a disability and then they have to adapt. So, even if they think it doesn’t affect them it could one day. I watched the documentary Crip Camp right after it came out and there was a lot of info in there that, watching that documentary, was the first time I had heard of some of those events happening. That’s the information I feel like should be taught in schools because it was a civil rights movement, and it’s ongoing. I felt ashamed as someone who tries to speak up for little people that I didn’t know certain things that had happened.

Bekah: Right.

Jillian: Did you watch the documentary?

Bekah: I did. To see how much I didn’t know was very shocking. I watched it alone first and then I watched it with people and they were like “Oh my god. But you knew this, right?” And I said “No. I do what I can because it’s my legit experience but this isn’t broad knowledge to people. We don’t learn about this.”

Jillian: Exactly. I talk about what I know. I haven’t watched it with my mom yet, I’ve been meaning to...She’s told me that she didn’t know 25 years ago, focusing on little people, the m-word was actually offensive until she went to an LPA convention for the first time. She didn’t know that was not just the wrong term but how offensive it really is. Now, everyone should be aware that that word is derogatory and demeaning.

Bekah: Right.

Jillian: I do want to talk about fashion for a brief second because that’s how my blog got started and then it morphed into something bigger. Do you think the fashion industry is becoming more accessible to people with disabilities?

Bekah: I think it is. I think it’s a long time coming and it’s definitely a slow process. I think that, for a while, fashion was able to write itself off as being adaptive or accessible without pointing out that accessibility does look different for literally every person. I think places and things could claim accessibility when maybe it was accessible to one group or one type of disabled people. In recent years it’s definitely growing and I’m personally seeing, through my feed and the people that I follow and am friends with, a lot more diversity within fashion which is really exciting. But, I do think it’s been a long time coming and maybe they claimed that they were something before they should have claimed it.

Jillian: Do you think clothing should be covered under the ADA? Do you think fashion designers should be compelled [by law] to start making their clothing more accessible?

Bekah: I think that if it were that would at least, whether or not they do it, to start thinking about it in their everyday life. Yes, if it’s going to make clothes more accessible I’m here for it. There’s no rulebook for fashion, obviously, but to find some sort of standard for diversity within all aspects of the fashion industry and to grow it out of that and base it on the guidelines of the ADA because accessibility is a necessity.

Jillian: On job applications they always ask “Do you have a disability?” and the options are yes, no, or not to disclose. Did you ever feel like you had to choose not to disclose [being disabled]?

Bekah: Out of high school and into my first couple years of undergrad I probably did, or if it asked me I just didn’t disclose. I think now, in just about every cover letter I write, I include the fact that I am disabled and queer. Most of the work I do is around those circles anyways, but I don’t think there would ever be a job application now that I go for that I wouldn’t openly disclose that information.

Jillian: I went through the same thing. There was a time towards the end of college when I was looking for internships and I didn’t want to lie and say no but I just couldn’t disclose and I hid anything that could imply that I was disabled. But, when I started looking for jobs, I was like, “Why am I hiding this?” It is what it is, I would rather them know up front, but I was at the point where I just wanted to get in the room and, not knowing if disclosure would be a barrier, I didn’t know what else to do. Do you think job applications should ask that regardless?

Bekah: I think so. I think, also, when you are disclosing that you are disabled, obviously there’s a fear of being hired for the token of it being brought up. I think nowadays, with this movement being re-energized, it would only be helpful for employers to ask that question. But also to ask that question where if an applicant chooses not to disclose that information then that’s okay.

Jillian: Exactly. It can’t be held against them if they choose not to disclose. Who inspires you? Who do you look up to? Who do you follow?

Bekah: One of my closest mentors is Rebecca Cokley ( Director of the Disability Justice Initiative at the Center for American Progress). My mom and her mom were really close friends and she was, when I was little, a big sister to me. Now that I’m an adult who is looking into the world of politics she has really been somebody that I’ve followed and learned a lot from. The first couple of trips I took out to D.C. I stayed with her and learned the random ins and outs of the system and how even our Capitol, whether it’s physically or logistically within the way that the processes go, is still incredibly inaccessible.

I definitely look up to Sinéad Burke as a powerhouse in so many different ways. The things that she does that covers so many different fields is just incredible. I think that those two as far as LPs go, and ones I can think of that are close to me in like a personal relationship, I’ve definitely learned a lot from those two women in the last five years.

Jillian: What are the changes, moving forward as various civil rights movements gain momentum, you hope to see?

Bekah: I think, because we are in the middle of a global pandemic and a national uprising, it will be easy to watch things fade and watch the news no longer focus on things. I’m hopeful that the momentum stays. I mean, it’s clear that there wasn’t focus on momentum post Crip Camp happening, because had there been or had it been listened to we would have read about it in textbooks. So, I do really hope that the momentum keeps this going. As far as our systems and the way that we run as a society, I think that now is a really crucial time to look all the way into the basic foundation of that and see where the changes need to be made because it’s obvious that they do.

Jillian: If you had to give advice to an able-bodied person about how to be a strong ally to the disabled community, what advice would you give them?

Bekah: I think, in any identity, what any ally should be doing is listening first. Just listening can be a really beneficial tool as an ally. Also, learning to get comfortable even though you’re not part of this population, pointing out when things are inaccessible and not letting it go under the radar if a disabled voice isn’t around to point that out. The work doesn’t, and shouldn’t just be on disabled folks. If you are seeing something that is clearly inaccessible, having the comfortability to name that and say that out loud is really beneficial too.

Thank you so much Bekah for taking the time to speak with me. I am continually inspired by you and your advocacy for the disabled community.

The ADA is a landmark piece of legislation, but it is not enough. People with disabilities comprise the largest minority in the world yet we are still grossly underrepresented in nearly all aspects of society. The disability rights movement did not end in 1990, it is ongoing and it is unstoppable.

LEARN MORE:

ADA.gov

Disability Rights Fund

Follow Bekah On social media:

Additional information:

American Association of People With Disabilities: ADA 30

ADL: Disability Rights Movement

Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution

NY Times Op-Ed: We’re 20 Percent of America, and We’re Still Invisible